Zhang Tongyu, 2024-05-17 18:30 Beijing

"100 Years of Neurological Intervention" will be the first scientific documentary to systematically show the human struggle between human beings and cerebrovascular diseases with 6 episodes of 15 minutes each. The whole movie will be narrated by top medical professionals from different countries, reviewing the vicissitudes of neuro-intervention in the past 100 years, showing the most advanced medical science and technology, and revealing the mystery of neuro-intervention surgery. In addition to presenting the scientific content objectively and realistically, the film also focuses on the exploration and discovery of young and middle-aged medical workers in clinical practice and technological research; at the same time, it connects the arduous process and important achievements of the old generation of medical doctors and scientists in scientific research and practice in the past 100 years, reflecting the scientific spirit of the medical workers and scientists, who are persistent, innovative and hard-working.

I am honored to follow the documentary film crew to visit the footprints of the development of neurointervention in Europe, the roots of this tour include four stops: Portugal, Germany, France, Italy. As a neurosurgeon/neurointerventionist, the museums and neurointerventionists that I am going to visit will be an indispensable treasure in my life. The following is what I saw and heard during the filming process with the program team.

Second stop--Germany

Germany was our second major stop, during which we had to go through Berlin, Stuttgart and Bochum, to visit three experts of different ages and backgrounds, who would interpret the significance of neurological intervention in stroke diagnosis and treatment from three different perspectives.

Berlin Cathedral

Stuttgart Palace Square

Grassland along the road in Bochum

Our first stop was Berlin, the capital of Germany, where we were to visit another master who is known to the world as the"Father of Pathology". Almost everything in his life was housed in this Medical History Museum located in the Medical School of Charité University. But it was exactly one of our most important stops in Germany.

Charité University Medical School

Charité University Medical School

I’m sure many of you with a background in medicine or biology have seen this picture. The lecturer in it is him,Rudolf L.K. Virchow (1821-1902).

Rudolf L.K. Virchow lecturing in the classroom

His relationship with neurological intervention went back to the mid-19th century, when Prof. Virchow first discovered acute thrombosis and confirmed its relationship to cerebral infarction. In fact, in ancient Greece, there were already records of such ischemic stroke patients, who suddenly fell to the ground and unable to speak or paralyzed after waking up. It is now clear that this is probably a manifestation of acute ischemic stroke, which is summarized by the Emergency Green Channel as the FAST Principle (Face: Facial Paralysis; Arm: Limb Weakness; Speech: Slurred speech; Time: Rapid Assistance)so that the population could go to the doctor more quickly, but this mechanism was unknown to the people at that time.

In 1845, Prof. Virchow was surprised to find that patients with gangrene of the legs often died of heart failure or stroke through pathological autopsy, which he speculated was related to the dislodging of blood clots in the vessels of the lower limbs blocking the cardiovascular vessels. And in 1856, through a case of carotid artery thrombosis with ipsilateral blindness, verified the hypothesis that thrombus dislodgement caused infarction. Later, in 1860, Prof. Virchow led his students to prove the relationship between thrombosis and cerebral infarction again through animal experiments. This also laid the pathological foundation for our neurointerventional treatment of acute thromboembolism, and the cause of removing thrombus in full swing was carried out.

Therefore, our current visit to his museum was straight to the subject of thrombosis. However, the preparation for the interview was difficult. Judith Hahn, the person in charge of the museum, who is a doctor of medical history and the director of the Museum for the History of Medicine in Berlin, couldn't speak English well, so we had to hire a German student to translate for us. But he was very shy and did not major in medicine, so we had a lot of trouble communicating with him at first.

Prof. Judith Hahn being interviewed

In the process of communicating with her, I fully understood the strictness (seriousness!) of a German. I was able to understand the strictness of a German (more serious!) in the communication with her. It took dozens of e-mails and even a video session before we were able to finalize the outline of the interview. However, she still insisted that we needed to come to confirm which pathology exhibit the thrombus is in person. According to her, Prof. Virchow has so many pathology specimens that it is hard to find the exact one. As a foreign interview team, she understood that we had traveled a long way to get here and gave us special permission to come in one hour before the opening to film, but as soon as the opening time arrived, we had to leave immediately. And we must told her in advance which one or which exhibits to shoot because she needed to apply to open the cabinet. For this reason, we had to divide into two days, every day at 9 o'clock dusty carrying heavy camera equipment to shoot, and then at 10 o'clock when the rules were asked to leave. Of course, unlike the Moniz Museum, there are student tours here every day, and the basic education in the German medical school can be seen. Luckily, when we actually saw the exhibits inside, we knew our trip was worth the effort.

Virchow's desk and some skull specimens.

And we found the blood clot specimen, the destination of our trip, among the whole floor of human specimens. At the same time, there were some unexpected gains: we also saw more aneurysm specimens, intracranial blood vessel specimens and so on. Due to space limitations, I won't show them all here.

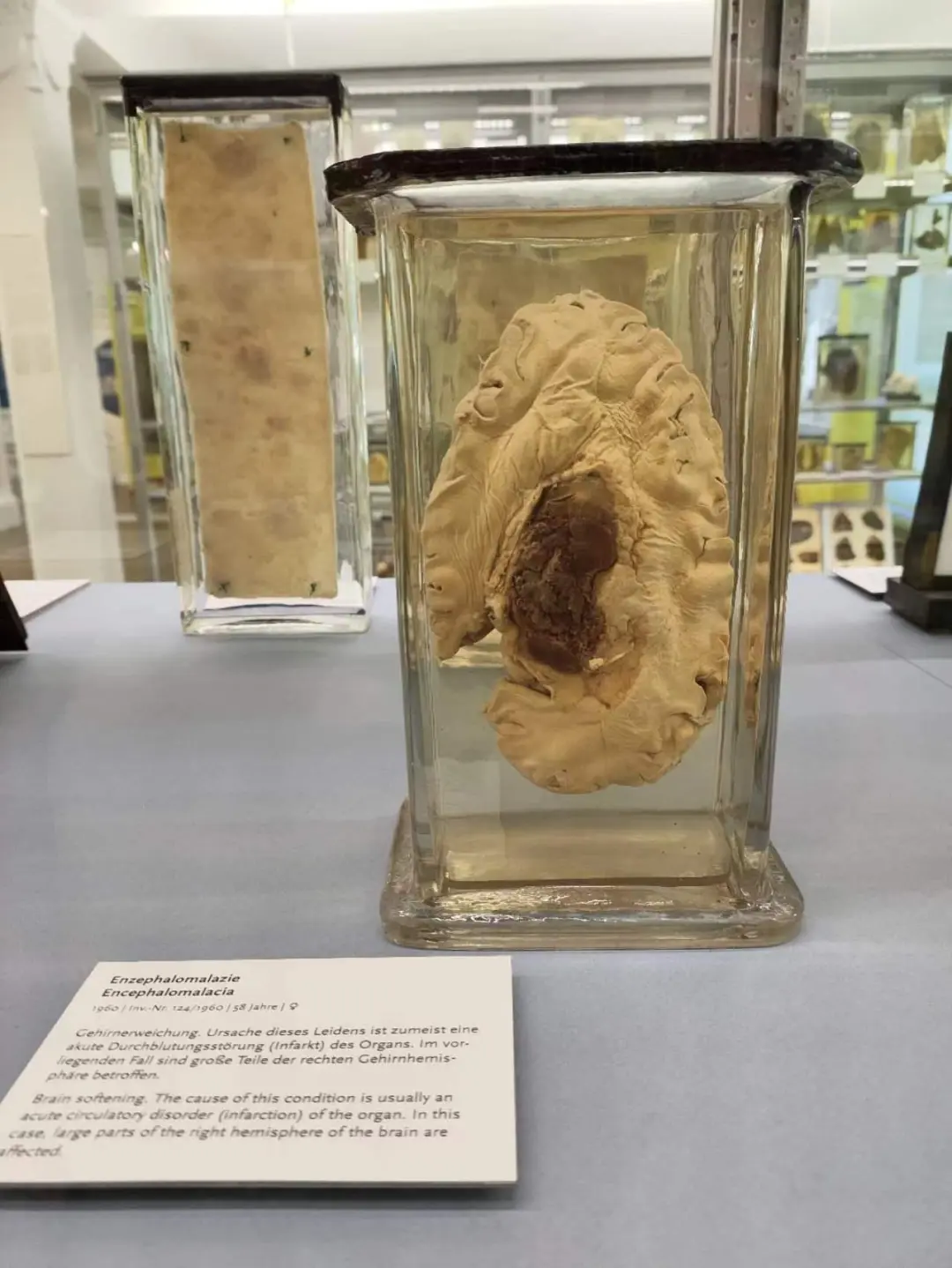

Brain tissue specimen of a patient with cerebral infarction caused by intracranial thrombosis.

Brain tissue specimen of a patient with cerebral infarction caused by intracranial thrombosis.

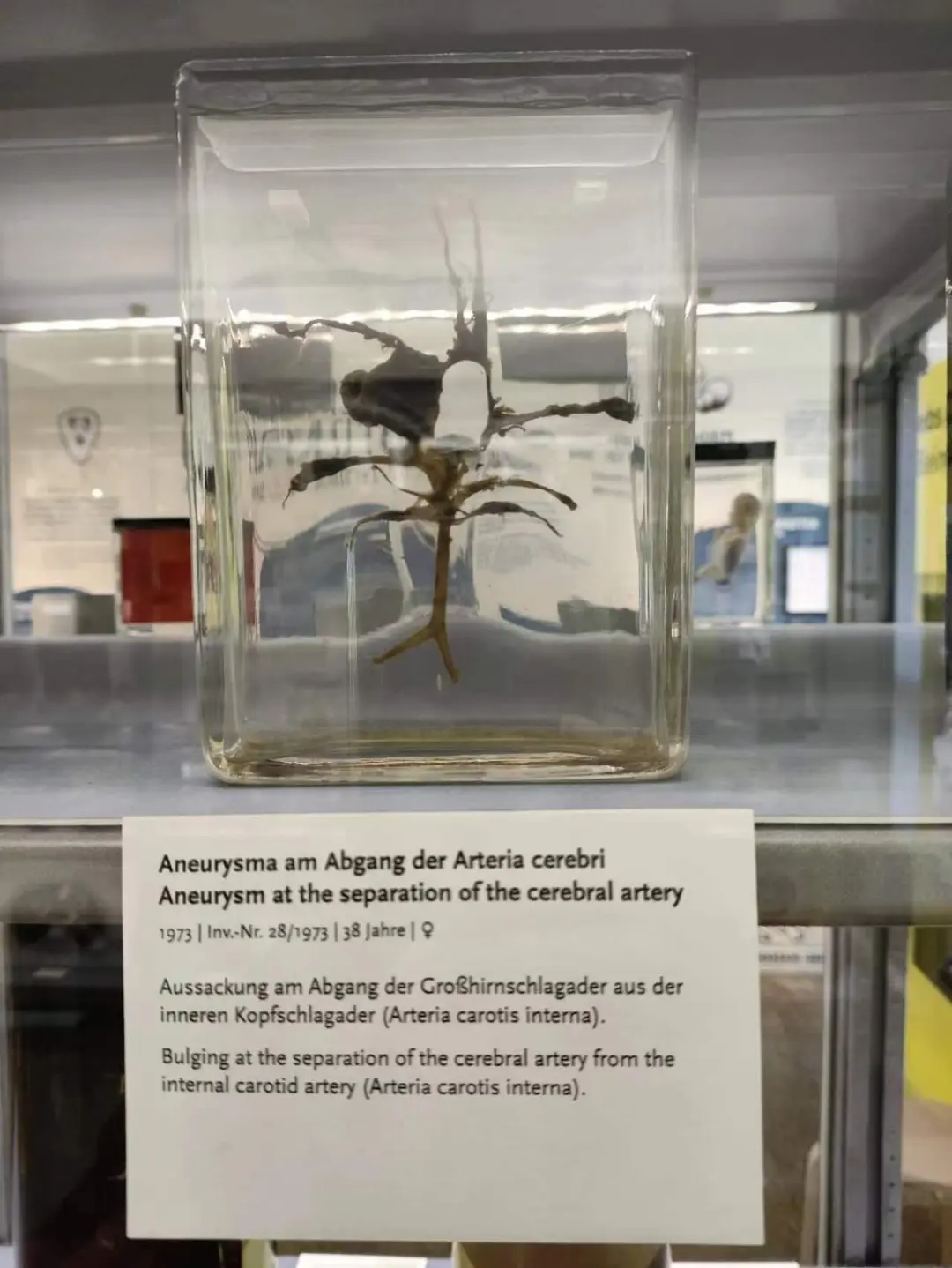

Blood vessel specimen of a patient with a large aneurysm of the internal carotid artery.

Blood vessel specimen of a patient with a large aneurysm of the internal carotid artery.

Visiting each well-made specimen in the museum is like reading the life of Prof. Virchow, savoring his dedication and greatness, and paying homage to each resting soul! Prof. Virchow was finally bedridden with a fractured femur in 1902, and died of heart failure eight months later, probably from a pulmonary embolism caused by a dislodged vein thrombus in his lower limbs, which is saddening.

Prof. Virchow's statue and the exhibition hall.

Prof. Virchow's statue and the exhibition hall.

After saying goodbye to the Berlin Medical History Museum, we went to our next stop, Stuttgart, the city of automobiles, for our next stop. Here we were going to meet a locally and world-renowned expert, Prof. Hans Henkes, who is the director of the Neurointervention Center at the University Hospital of Stuttgart, and is better known as the first person to use the Solitaire AB stent to extract thrombus. When we first met him, he had just come out of a surgery and was very busy. But he was prepared for our interview.

Prof. Henkes just came out of surgery

Prof. Henkes just came out of surgery

When I thought this would be a hurried interview due to the busy schedule of the expert, he had already changed into a suit and stood in front of us with the prepared manuscript. A unique elegance from a German gentleman came out and proved once again that you should never underestimate the rigor of a German.

Henkes changed into a suit and prepared for the interview

As mentioned before, we interviewed Prof. Henkes because he was the first doctor to use the Solitaire stent for arterial thrombolysis. Although devices such as the MERCI, CATCH, and pCR had been used for thrombolysis at that time, the recanalization rate was less than 50%, which was not as effective as the later Solitaire AB. The Solitaire stent is actually a long-established intracranial stent that was designed to assist in the embolization of intracranial aneurysms due to its strong support and retrieval, but because of the stent's good support and the stiffness of the entire system, the actual effect of assisting in the passage of tortuous intracranial arteries was not very good. However, the stiffness of the stents resulted in better riveting and gripping ability, and the stents themselves were retrievable, a feature that Prof. Henkes applied to make a difference in ischemic cerebrovascular disease aortic embolization. Fortunately, the first patient was invited to be interviewed. She and Prof. Henkes recalled that she was 67 years old at that time, with sudden hemiparesis and poor speech, and was admitted to the hospital 3.5 hours after the onset of the disease, and the angiography showed acute embolism of the left middle cerebral artery at the section M1. The patient immediately resumed physical activity after surgery, and her speech was slowly restored in 1 month after the surgery, and she is still living a healthy life. Even though it has been more than 10 years since the surgery in 2008, the patient and her family still can't help but be in tears when talking about this time, and keep expressing their gratitude to Prof. Henkes. Long-term follow-up communication has created an enviable doctor-patient relationship.

Prof. Henkes talking to the first Solitaire thrombolytic patient.

Prof. Henkes talking to the first Solitaire thrombolytic patient.

After the interview, Prof. Henkes continued his surgery and he said he has many daily operations, sometimes up to 20 treatments a day! We were allowed to film an intracranial unruptured aneurysm procedure with the consent of the patient.

Prof. Henkes treats an intracranial aneurysm with a dense mesh stent.

Prof. Henkes treats an intracranial aneurysm with a dense mesh stent.

Nowadays, there is a proliferation of interventional materials, and blood flow-directing devices (dense mesh stents) are now gradually becoming the mainstay of treatment for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. They are more aggressive than we are in the use of mesh stents, even for relatively small aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery or anterior cerebral artery they prefer to use mesh stents to solve the problem, whereas in our country we are still more conservative, after all, we are worried about thrombotic events. Maybe it's the advanced materials, maybe it's the ethnic differences, but they don't have a higher rate of thrombotic events without the enhanced antiplate. This difference is what makes sense today when we do multicenter and even multinational RCTs.

Prof. Henkes is also a clinician-scientist who still works closely with the team that developed the Solitaire stent, which has now become independent from the original company and continues on the path of stent development. Prof. Henkes showed us the results of their research on the p64 and p48 dense mesh stents, which are currently widely used in Europe but not yet available in China. Our department is honored to be the research unit for their pre-market study in China, and we are looking forward to the good results.

Clinical Trial Launching Meeting of p64 and p48 dense mesh stents

Clinical Trial Launching Meeting of p64 and p48 dense mesh stents

Taking a photo with Prof. Henkes

Taking a photo with Prof. Henkes

With the introduction of Prof. Henkes, we went to Bochum R&D base next, and at the same time, we also wanted to meet his old friend Prof. Hermann, who has been cooperating with us for many years. Although Bochum is a small town in Germany, it is also very beautiful. The company we interviewed is called Phenox, a well-known interventional device manufacturer, and Prof. Hermann is the owner and chief scientist here, as well as an expert in biomedicine and materials medicine. We were warmly received upon our arrival. Prof. Hermann and his team simulated the whole process of intracranial stent implantation and retrieval for us in the lab, and explained each step in detail.

Model simulation of stent retrieval process

Model simulation of stent retrieval process

Prof. Hermann explains the stent retrieval process

Prof. Hermann explains the stent retrieval process

Afterwards, Prof. Hermann further demonstrated the whole process of their production, research and development, not only let us have the opportunity to participate in their R&D discussions, but also made an exception and allowed us to enter the factory to feel how a stent is produced.

Roundtable discussion with Prof. Hermann's team

Roundtable discussion with Prof. Hermann's team

Prof. Hermann demonstrating the stent production process

Prof. Hermann demonstrating the stent production process

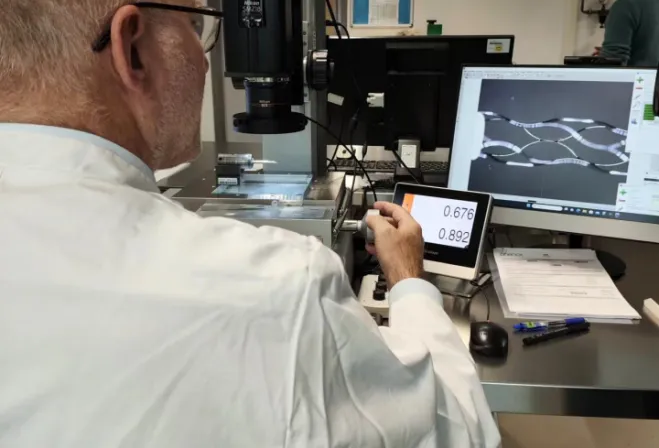

In the R&D center, I felt like I saw the epitome of the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Science and technology are the first productive forces and the source of all innovations. Although we are the end-users of these devices, we often do not know the true colors of the mountain. It was not until the moment I saw them under the microscope that I really understood what kind of structure the so-called braiding and laser engraving really is, allowing us to understand it better and use it better on patients.

Prof. Hermann showing details of the stent

Group photo with Prof. Hermann (center) and Chief Engineer (right).

Advances in medical care depend on the improvement of our doctors’ surgical skills, but even more so on the innovation of treatment means. With the continuous innovation of interventional devices, more and more neurosurgeons have started to pay attention to neurointervention in both hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes, and have carried it forward in the clinic, such as ISAT (Prof. Andrew J Molyneux's team at the University of Oxford, UK), DIRECT-MT (Prof. Liu Jianmin's team at the First Affiliated Hospital of the University of Naval Medical Sciences, China), CASSISS (Prof. Jiao Liqun's team at Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University), and BAOCHE (Prof. Ji Xunming's team at Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University) who have pushed interventional therapy to a climax, gradually replacing traditional craniotomy or internal medicine as the mainstream treatment.

Any use of this site constitutes your agreement to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy linked below.

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "China-INI," "chinaini.org" are trademarks of China International Neuroscience Institute.

© 2008-2021 China International Neuroscience Institute (China-INI). All rights reserved.